Marshall Nych

Marshall Nych’s habitat is a family farm in New Wilmington, PA. When Marshall isn’t writing outdoor humor, he is an elementary teacher misguiding the youth of Mercer County. Although Nych has fished 15 states and 4 countries, his best catches remain his wife and daughter.

I Love a Parade

By Marshall Nych

October was just a week old. The crisp, cool autumn air filled my lungs with hope, life, and purpose. This archery season promised to be a good one. Unbeknownst to me, it had its fingers crossed!

October was just a week old. The crisp, cool autumn air filled my lungs with hope, life, and purpose. This archery season promised to be a good one. Unbeknownst to me, it had its fingers crossed!

On Friday night, I had planned an evening hunt with my bow, favorite stand, and the many deer on our family farm. However, my devious little sisters, Gigi and Krissy, had other plans. They insisted that either my father or I take them to the West Middlesex Homecoming Parade.

“All of the popular kids will be there,” cried Gigi.

“Yeah. We have to go,” snapped Krissy.

Ironically, my own sisters were becoming less popular with me by the second. I do not believe they cared.

Looking towards my father and I with her patented puppy dog eyes, Gigi said, “One of you has got to take us!”

I looked to my father, the head of the household, who always used good judgment to make the right decision. My dad immediately grabbed his hunting gear and headed for the door.

“Have fun with the girls Marshall,” Dad snickered.

Speaking of Snickers, the only comfort I managed to find was that I might get some sugary loot from this parade. I grabbed three large feedbags from my grandpa’s barn and the three of us were off to beautiful downtown West Middlesex.

Gigi, Krissy, and I arrived along Main Street at about the time I should have been arriving to Gitmo (our farm’s deadliest stand.) I am still trying to figure out why West Middlesexuals (that is what someone from West Middlesex is called) decided to call it Main Street. The road hosts dilapidated, cracked sidewalks that connect the school to Dairy Mart and Dairy Mart to our only local bar, the Bear.

As the parade began, I had deer on my mind. I constantly glassed small yards and glared onto porches in search of the elusive whitetail. Various organizations floated by our sidewalk stand. I quickly made an observation. Most of the people in the parade were old! Old men made up the entire local VFW float as well as the neat little Zem Zem cars. I wouldn’t have considered this observation such a bad thing if old men actually knew how to throw candy.

Our feedbags were still empty when the Homecoming Court convoy drove along Main Street. Most towns have future queens perched upon Corvettes and other fine sports cars. I have shared with you just how different West Middlesex is. Our teenage royalty rode shotgun in rusty trucks or on top of dusty tractors. One young lady was in something close to a Corvette…she was nestled in a Coronet. I was a little disappointed (mainly that none of the sweethearts threw any Sweet Tarts!)

Gigi, Krissy, and I knew the goodies were about to show up! The West Middlesex Volunteer Fire Department always drove their fire engine through the parade and has amassed an indisputable reputation for giving the most grub.

There hadn’t been too many fires to fight, so the firefighters, having nothing better to do, pulled out all of the stops for this year’s Homecoming Parade. The entire volunteer crew volunteered to dress like circus clowns as they made their parade appearance. The uniformed firefighters hid behind white makeup, red noses, and fuzzy wigs. This made me question both the quality and sanity of our “homeland security.”

Just before the big red fire truck had made its way to our spot in front of the convenience store in a one-convenience store town, the sirens went off with an eerie authenticity. Suddenly, the clowns did not seem so friendly. Worse yet, the volunteer crew quit throwing their handfuls of Smarties and Snickers.

Apparently outside of town Old Man Burns’ barn had caught on fire while he was smoking one of his cheap cigars. The fire truck was summoned immediately. This tidbit was not revealed to the rest of West Middlesex…especially the small children who wanted candy! The crew jumped in the truck and hit the gas. The screaming truck (the screaming was from the clowns, not the truck) swerved between the marching band and the Zem Zems trying to escape the very parade that gave them their annual supply of fifteen minutes of fame.

Little kiddos were racing onto the road thinking that the fire truck would reward them as it had in parades past. However, it nearly turned them into small pavement pancakes instead. Clowns were cursing and throwing candy way up in the trees to lure the children and me off the roads. This ploy worked for most of the kiddos…not me.

The West Middlesex Volunteer Fire Department finally succeeded in its exit and arrived to the flaming barn. According to the newspaper, they did a fine job extinguishing the blaze. I would have given up another night of hunting and my empty sack of candy to see the look on Old Man Burns’ face when a truck full of clowns pulled up to his barn!

Marshall Nych’s habitat is a family farm in New Wilmington, PA. When Marshall isn’t writing outdoor humor, he is an elementary teacher misguiding the youth of Mercer County. Although Nych has fished 15 states and 4 countries, his best catches remain his wife and daughter.

Tinkering

By Marshall Nych

“To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering,” wrote Aldo Leopold, the Father of Conservation.

I am uncertain as to how smart my starts with reloading have been. Still, I have eagerly begun tinkering with this explosive hobby. Before I even unscrewed the cap from the gunpowder or secured reloading tools to my bench, family members left hints and innuendos of their preferred load. The variety was astonishing. I could toil away the duration of a life’s work and die before amassing so many dies.

I discerned much can be learned about a person by the gun they carry. Say the chap has a fine, one-of-a-kind Italian over and under. Though the man is classy, well educated, handsome and successful, he isn’t the kind of guy you’d want to have a beer with. For starters, the gentleman doesn’t drink beer. Probably Scotch. A strong foundation requires common ground. Good looks and smarts, I see no parallels.

Then there’s the guy with a beat down, scratched up, dented in12 gauge. This is the kind of man fearlessly getting his hands dirty. In fact, the shotgun he carries gets the brunt of grime before making it to his hands.

This tribute celebrates not only the sport of shooting and follow-up art of reloading, it also commemorates the caliber of characters and rifles hunting various limbs of my family tree. I welcome the reader and reloader alike to draw their own conclusions and sight in their personal firearm identity.

A good place to start is at the top. Perched on the pinnacle is the patriarch. Grandpa prefers his .30-40 Krag. The rifle dutifully served in the military during the World War. From there, it was sentimentally handed down from Papa’s older brother Jule, a soldier in the Army. Grandpa aimed small and missed seldom. The only drawback of the .30-40 Krag would be reloading. If it took as long for the United States to win the war as it did for me to track down dies, our country would be in trouble.

A good place to start is at the top. Perched on the pinnacle is the patriarch. Grandpa prefers his .30-40 Krag. The rifle dutifully served in the military during the World War. From there, it was sentimentally handed down from Papa’s older brother Jule, a soldier in the Army. Grandpa aimed small and missed seldom. The only drawback of the .30-40 Krag would be reloading. If it took as long for the United States to win the war as it did for me to track down dies, our country would be in trouble.

My father is most himself when toting a .50 caliber flintlock. Personally, I believe this has something to do with his knack for procrastination. Every fall finds Dad’s bow a varying degree of unprepared. Father had never got around to sighting it in, didn’t have enough arrows, or pulled another excuse from his quiver. Eternally distracted by the calls of nature, Dad never seems to dial in his rifle for firearms season. Hence, an annual tradition has become my father forced afield by late season flintlock. Do not be fooled by his early season apathy, the man punches tags faster than a railroad ticket taker. Last winter, Dad filled three deer tags in as many days. Two of the deer were harvested in back-to-back drives.

Cousin Grizz carries a .30-06 with cheap optics. Ironically, between his ears, he too dons cheap glass. Duct tape has been trusted to hold eyewear together and/or to his face. Most hunts are riddled with losing or cracking one form of optics. Arguably, with a nickname stemming from a bruin, my cousin wants to be prepared for any beast encountered in the wilds of Pennsylvania. A .30-06 provides desired comfort. Plus, ammo and reloading resources are readily available.

Jim, my father-in-law, watched one too many spaghetti westerns as a kid. Consequently, the first side effect is Jim requesting pasta with every meal. The second drawback would be the fact he only shoots cowboy style .45 calibers. My dear father-in-law promised the next gift he gets me will be everything I need to properly stock his shelves.

Cousin Lou’s favorite rifle happens to be a .270. Lou has taken his fair share of deer with this flat shooting caliber. My cousin says he depends on a caliber quick enough to dispatch a raging bull. He is a dairy farmer. I only know his preferred diameter because it’s what I shoot. Though I have tried, Lou never bums me a bullet. Imagine my fellow shooter’s surprise when I go from freeloader to reloader.

Younger brother Ryan opts for a 30/30 lever action. Less of a personal choice, little brother went with the bullet bestowed by Dad. Still, years of missing has honed Ryan’s skills with the lever considerably. Coupling his poor shooting with his quick action, I predict the 30/30 will be my most prolific reload.

As I mentioned earlier, my favorite caliber is a .270. Older brother Nate, who is fueled by a burning sibling rivalry, always needed to top his little brother. Perhaps this is why he fires a .280. Big brother has a one-hundredth of inch bigger gun. If my .270 reloads do not fit his Remington, it’s not a little-gun-toting little brother’s fault.

Give me one each of the following and I will hunt happily: shotgun, big game rifle, twenty-two, muzzleloader, and handgun. I am far from a shooting expert. Unless the readership is one, it is impossible to understand or reason with the pros.

If there are 5 men in a room, logistically and mathematically, there could be 10 different handshakes. However, place 5 gun experts in the same space and the combinations are infinite.

Expert Quote 1: “On a cloudy day, I like to carry my .243, open sight of course.”

Expert Quote 2: “Tomorrow is the autumnal equinox, better go out and treat myself to a new insert make, model, and caliber.”

Expert Quote 3: “Slacker! I already have that one in wood and synthetic stocks each with stainless and blued barrels!”

The saying goes, give a man an inch and he will take a foot. I have found give an authority on guns a yard and he will show up with a bazooka. The evolution of a rifleman starts at a young age with a slingshot or Daisy. From there, one evolves decades across fine shotguns and vintage classics. At some point, one starts tinkering with reloading.

Marshall Nych’s habitat is a family farm in New Wilmington, PA. When Marshall isn’t writing outdoor humor, he is an elementary teacher misguiding the youth of Mercer County. Although Nych has fished 15 states and 4 countries, his best catches remain his wife and daughter.

Still Beating A Dead Horse

by Marshall Nych

There is nothing I hate more than sequels to hit movies or popular television programs ending with “to be continued…” I also despise when a fine literary trilogy is somehow morphed into seven Hollywood movies. Hypocritically, I did feel the need to provide an update on a prior story. If you are amply unprivileged and unfortunate, you may have read “Beating a Dead Horse” from my 2nd mistake of a book Field Tested: Back to Abnormal.

There is nothing I hate more than sequels to hit movies or popular television programs ending with “to be continued…” I also despise when a fine literary trilogy is somehow morphed into seven Hollywood movies. Hypocritically, I did feel the need to provide an update on a prior story. If you are amply unprivileged and unfortunate, you may have read “Beating a Dead Horse” from my 2nd mistake of a book Field Tested: Back to Abnormal.

For those who have enjoyed peace, happiness, and sanity up to this point, here’s a quick recap: An eccentric lady, Gertrude, moved herself and thirty some horses from New England to our western Pennsylvania farm. Gertrude enjoyed the humanitarian prestige and high public opinion more than actually caring for her horses or shoveling their exhaust. Gertrude elegantly named all of the horses after her favorite pastime – hard liquor.

One character forgotten in the pages of the first story was her enslaved boy. He was likely in hiding when I twisted the original tale. Whether he was a son, other relative, hired hand, or kidnap victim never was clear. As I sit here now, I can still hear Gertrude holler his name across our fields. What was it? I know it started with a B. Oh yes…

“Get ta’ work B-A-R-N-Y!”

Barny, I am left to assume, was short for Barnacle.

So the crazy horse lady and her equally crazy horse boy continued their equestrian quests following the controversial, publicized demise of their prize horse Kaluha. Though four digits richer after cashing the check from the Humane Society, the pair quickly became unstable once more, unable to tame the wild debt owed to my grandparents. Monthly rent came yearly. Money for oats and hay, which should have arrived in a bale, came in grain-sized increments. The amount of time, energy and sheer creativity, the duo put into their excuses was admirable. If Gertrude and Barnacle would have harnessed this evasiveness into work, they could have really done well in life.

Perhaps that was part of the problem. Gertrude enslaved Barnacle to do all of her dirty work with the horses. Dirty work with horses ends up being all work with horses. The problem was Barnacle hated all forms of work. The boy put constant effort into avoiding his greatest fear – a job. The only finger I ever saw him lift was his social one. He showed it to me a couple of times. No one ever accused Barnacle of being a nice kid. At the boy’s idle leisure, the horses suffered.

Around the peak of Barnacle’s equestrian apathy, my father-in-law Jim and I were working around the farm. As luck had it, we were able to use my truck to complete the tasks that particular day. With all of the work, I had forgotten about the deepest rut on the back forty. As I hit the chasm going full speed, Jim and I were taken aback when a “YELP!” erupted from the bowels of my truck. Upon investigation, we found the horse-boy-stowaway in the bed. Unbeknownst to us, we had been Barnacle’s taxi all day, making his chores far less laborious. Had I known Barnacle had attached to my Chevy, I would have embraced and sought out every one of my farm’s delightful features.

It was quite common, after a day in and around the farm, to drop the tailgate and find Barnacle had covertly placed feed, fence, tools, and other symptoms associated with Gertrude’s horse disease. I found little comfort in knowing I helped haul Barnacle’s junk.

I tried to lie to myself that by helping the lethargic troll, he could do a better job caring for the horses. At the fingertips of his handiwork, the herd escaped as frequently and reliably as Houdini. The horses looked at the fence Barnacle haphazardly erected to be as threatening as marshmallows. Gertrude’s entire top shelf brands of liquor poured into my garden and spilled through my landscaping as they pleased.

One June, various uncles, aunts, and cousins were stacking hay bales in the barn. Below the barn is where Gertrude stabled some of her victims. Grandpa had noticed stacks of hay getting shorter. While we tossed bales to one another, the imp climbed through a small opening. Barnacle was just as surprised to see us as we were to see him. Mystery solved…to avoid walking across the property and carrying hay to the horses, Barnacle simply pushed the stolen hay from Grandpa’s barn. The horse boy was so lazy he made gravity feed the herd.

Upon us catching him in the act, Barnacle clung onto desperation and offered to do a couple hours of work. Knowing full well his couple hours would be worth a couple of minutes, we let him go. Our family simply added it to his tab.

Approaching a $4,000 debt, my grandparents applied some pressure to these festering wounds. More importantly, Grandma did not want associated with a herd of horses that had the health and disposition as one residing in the town where Purina and Elmer’s factories were found. Secretly, Gertrude cooked up and stuck to a plan involving a West Virginia escape. The last invasive species the wild and wonderful state needs invading were Gertrude and Barnacle. West Virginia would be forced to add wacky to the state motto.

Oft we have heard the saying pertaining to riding a horse off into the sunset. Gertrude and her imbecile boy waited a few hours after sunset. In the middle of the night, it required two fools to take one foal each mission. Their goal was to sneak off the farm, one horse at a time.

The Nych family was well aware the horses were slowly dwindling. We were reveling in the fact. Some of the cousins were even thinking about showing up one midnight to help speed up the secret operation. Tough Guy even considered giving Gertrude the four grand to just disappear.

Still investigating the mysterious death of Gertrude’s Kaluha, federal agents observed these late night escapades. Before long, two officers appeared on Grandma’s front porch. The closest the agents’ spotless, clean-cut look fit in was about an hour’s drive south.

Grandma, who smelled a problem through aromas of chicken soup on the stove, asked, “What kind of trouble did my boy get into now?”

The agents, putting away their perfectly polished badges, were caught off guard. The female officer said, “M ‘am, we are not here in regards to your son.”

“This time,” added the male officer.

The lady agent continued, “We are looking into Gertrude and her horse operation. Such mistreatment of horses is highly illegal…”

“And highly expensive,” interjected the man, likely sensing this was the kind of case you could retire on.

“The landowner can also be held liable in such investigations. It is in your best interest to sever any ties you have with Gertrude and her property immediately,” finished the agent.

“And that odd horse boy too,” added the male.

Grandma, with her uncommonly strong common sense, snapped, “It’s easier to get yourself in trouble abusing a horse than a child nowadays!”

Both agents, unable to argue, nodded then dismissed in unison, “Have a good day M ‘am.”

This little visit from the Feds was all the motivation Grandma needed to evict the future convicts. Gertrude, a few dozen mange-infested horses, and Barnacle fled to the wilds of West Virginia before the agents were able to catch them in Pennsylvania.

Justice prevailed. The local paper (perhaps another slow day in the news) reported Gertrude had been arrested and imprisoned for the cruel and unusual treatment of equine species. Her bail was set at $90,000 (a bit more than she owed us for our bales), thus confirming Grandma’s theory about animal and child abuse. Looking closely at her son Barnacle, one can see why law books were written in such a way.

Anytime someone found themselves behind bars in one of the old western flicks, there was usually a steadfast horse parked below the jail cell window. A posse then prompted the prison break with rope, which could somehow jeopardize the entire soundness and structure of any correctional facility. At this point, the prisoner would hop onto the horse and gallop towards freedom and a remarkable sunset.

Had Gertrude taken better care of her horses, perhaps there would be one willing to saddle up to the plot of her escape. Plus, the way she worked poor Barnacle, it’s no wonder he didn’t round up a posse and ample rope.

After Gertrude gets out of jail in 4 – 6 years, likely about 20 in horse years, the crazy horse lady will pursue greener pastures. Such fields, far from our family, will be without stallions, mares, or roans. However, there will always be one fool…a nag still beating a dead horse.

Marshall Nych’s habitat is a family farm in New Wilmington, PA. When Marshall isn’t writing outdoor humor, he is an elementary teacher misguiding the youth of Mercer County. Although Nych has fished 15 states and 4 countries, his best catches remain his wife and daughter.

Done Right

The classic adage reminds us, “If you want something done right, you have to do it yourself.”

The classic adage reminds us, “If you want something done right, you have to do it yourself.”

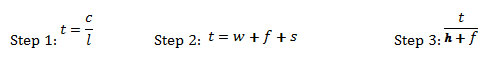

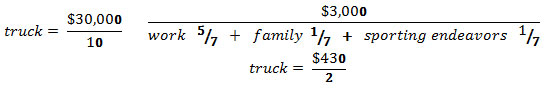

Nowhere does this bell ring truer than the outdoors. With no one is this chime heard with greater clarity than my father-in-law Jim Harper. Harper’s passion projects cover all of the elemental bases – reloaded shotgun shells are born for the air, homemade longbows are grounded on earth, and handcrafted kayak are destined for water.

Be it tinkering in his reloading den or toiling in his vegetable garden, the man’s meticulous attention to detail and dogged work ethic lead to a job done right. This knack for doing things the right way the first time has trickled into his outdoor passions and pursuits. His noteworthy successes with reloading, archery, and boating are welcomed side effects of skilled labor and countless hours mastering his perspective craft.

Half of Jim’s basement is dedicated to reloading. You name it, Harper can reload it. Family and friends alike depend on Jim to feed shotguns, rifles, and handguns. Overlooking tables of dies and tumblers are shelves of brass, lead, and gunpowder. Like a symphony, the ingredients work a concerted harmony in the name of shooting sport. Harper’s generous spirit, there is not a caliber he won’t shy away from to help a friend.

Some celebrate the holidays and share talents with a plate of homemade cookies. Jim starts from scratch with a different medium. He cooks a perfect batch of six shot. Dozens fill the vests of his hunting buddies. This thoughtful Christmas present oft leads to a Christmas pheasant.

With respect to reloading, there have yet to be dies matching the caliber of Harper’s character.

The other half of Jim’s cellar is devoted to traditional archery. Adorning the walls better than any wallpaper ever could are frames of arrowheads, pottery, and other Native American artifacts. When efforts of a farmer’s plow were washed by spring rains, Jim and his father would be there to work the fields. Like the Native Americans before them, their preferred hunting grounds were along Wolf Creek. Jim’s greatest find was an authentic axe head, his father’s a ceremonious eagle shaped piece.

When Jim wasn’t discovering archery artifacts, he was creating his own archery equipment. My father-in-law diligently watched for stands of Osage orange. Their bright staves were step one in the lengthy process leading to Jim’s finest bows. Dried wood was painstakingly shaped with the same growth ring on the bow’s long surface. Perhaps the bows Harper finished shared a birthday with the shooter. Regardless, Jim’s sweat fell atop the whitetail deer sinew, which wrapped tightly along the bow to strengthen it. The man even fashioned his own arrows, straight as anything found in modern bow shops.

While basement has been consumed by hunting, Harper’s garage pays homage to the aquatic world angling and boating. Amongst antique tackle and wooden plugs handed down from his father, Jim has honed his skills in boat making.

With craftsmanship second to none and strips of fine cedar, Jim assembled the most handsome kayak most have ever laid eyes on. From Lake Erie to local ponds, the perfect palindrome senses the pulse to any body of water. In fact, most times Jim slips into his kayak, many fellow sportsmen ask where he got it or, in a few cases, make Harper an offer on the spot.

With craftsmanship second to none and strips of fine cedar, Jim assembled the most handsome kayak most have ever laid eyes on. From Lake Erie to local ponds, the perfect palindrome senses the pulse to any body of water. In fact, most times Jim slips into his kayak, many fellow sportsmen ask where he got it or, in a few cases, make Harper an offer on the spot.

Such sentimental things cannot be fetched with a price. Our family tree must be a cedar, for the 15 foot vessel will glide as one with the water’s surface for generations to come. Only when Jim works the paddle, thrusting into the cool waters, is it noticeable the kayak and its passenger are only visiting guest.

A job done right tends to positively influence others. I for one have been graced with Harper’s touch. When upland bird hunting with Jim’s reloads, I hunt a little harder and forget the pain associated with Pennsylvania’s peaks. A grouse hunt holds more meaning if reloads are tucked in the barrel, side by side like Jim and I on the trail.

In stand with one of Harper’s fine longbows in hand, I exhibit the most extreme caution to promote ethical shots. I want justice for not only Harper’s handy work, but also the fine animals we have come to love.

Nestled in Jim’s kayak, I truly delight in my surroundings. Each time I find myself seated within such beauty, I cannot help but feel it helps me observe and appreciate nature’s beauty to a greater degree. Climbed into the boughs of the cedar, each and every cast is treated like a perfect or final one.

I have now had the honor of having Jim Harper in my life for more than a decade. Harper is a wonderful father to my wife and delightful grandfather to my children. In my experience, I have come to find if you want something done right, ask Jim.

Gertrude’s starving horses look happy.

I am confident to declare the most incorrect stereotype about hunters and fishermen is the assumption they are inhumane and care not for the welfare animals. In all seriousness, I must stress this is simply not true. On the contrary, sportsmen love animals so much, they spend ridiculous amounts of time, effort, and money trying to eat them.

I am confident to declare the most incorrect stereotype about hunters and fishermen is the assumption they are inhumane and care not for the welfare animals. In all seriousness, I must stress this is simply not true. On the contrary, sportsmen love animals so much, they spend ridiculous amounts of time, effort, and money trying to eat them.

I grew up in an area of Pennsylvania where work was a last resort. In fact, one afternoon while eavesdropping on a conversation about me, I heard my mother ask my father, “Is he crazy?”

“Marshall? Course not…he’s much too lazy to be crazy!” replied Dad.

Father was right. Crazy entails senseless action, much building, and much doing. In my relaxed neck of the Pennsylvania, we celebrate our laziness and will go to great lengths to secure it. For example, Pennsylvania is home to many deer. PA also has many drivers. It is nothing to see a deer alongside the road. In the battle between vehicles versus deer, the vehicle wins just about every time.

Traveling my routine route, one just pleasantly paved, I recently swerved around one particular case where somebody didn’t do their job and pick up the cervidae. No big deal. Laziness, in its purest form, is the degree to which people will do work to get around work. Upon my return, I observed a road crew painting the lines, taking measurements, and standing around in large chatty groups. As I approached where the deer and family sedan had battled, I couldn’t believe my eyes. There, right where I had seen it in the morning, lay a deer with two fresh yellow lines. I knew not to pass.

Let us lazily drift back to the family farm. My grandfather, one of the only hard-working men I have ever known, has diversified the farm. Unable to keep up with the high demands of a dairy farm, Grandpa began raising livestock and grain farming. In recent years, Grandpa began renting out small portions of land. One such renter was a lady who “rescued” old horses. Gertrude, a short, fat woman with more money than brains, was a bit of a hag herself. Gertrude started by stacking five or ten horses into the barn like sardines with manes. It wasn’t until she achieved piles of twenty that she began referring to herself as a selfless humanitarian.

Being a yuppie from the New England area, Gertrude cleverly named her horses after her favorite drinks. Guess what? Coffee, iced tea, or fruit punch did not make the list.

At the peak of Gertrude’s heroism, my family noticed one of the older horses, Kahlua, was constantly losing his balance. The entire neighborhood sadly watched Kahlua with a watchful eye…twitching, but watchful nonetheless. A concerned friend saw the old horse fall in the pasture just below my house. The Good Samaritan immediately attempted to contact Gertrude. Thankfully, I was not party to this conversation. I am confident it went something like this:

Phone: Ring…Ring…

Gertrude: Hello Darling!

Neighbor: Uhh…hi.

Gertrude: What is the meaning of this intrusion? I am enjoying the second half of a dry martini!

Neighbor: The glass?

Gertrude: No, the bottle.

Neighbor: Sorry, I just wanted to let you know that…

Gertrude: What a great name for my next horse – Martini!

Neighbor: …your Kahlua is not doing so well.

Gertrude: Drank that last night. Thanks Darling. Tata!

A couple of days later, just past the point when Gertrude figured her self-righteous prizes might be in need of water and food, Kahlua was discovered dead. One might think when dealing with the average horse whisperer, the sad event would be a peacefully silent and respectful tribute to remember the loss. Gertrude was not average. She was more of a horse shouter.

Gertrude failed to acknowledge the horse likely died of old age, rapidly progressed by the unsavory conditions she had created. Gertrude’s next step must have been to snack on some mushrooms in her horse pasture. Grand delusions immediately followed.

Gertrude dreamt up some crazy story. Her edition accused several local juvenile delinquents of tying up Kahlua. Once bound, she claimed they attached her horse to an all-terrain vehicle and inhumanely drug her through the fields. Hence, these hoodlums were responsible for his untimely demise.

There were more holes in Gertrude’s theory than in the entire field. The only juvenile delinquents around were my two brothers and me. Not only would we never do such a thing, we never owned such toys as an ATV.

Like I said before, Gertrude wasn’t much for whispering and saw this tragedy as a perfect opportunity to have her gracious, private acts of kindness be a little more public. Soon thereafter, Kahlua’s death made the front page of the local paper six times in just two weeks. I understand there isn’t very much to report in a small town, but Gertrude changed this one-horse-town into a thirty-horse town.

Either the reporter was talking about the wrong horse or stirred the facts up a bit. Bold headlines read, “The Friendliest Horse Ever. Loved Children.” I just remember Kahlua chasing me around the pasture, biting one sister’s hand as she offered a carrot, and kicking my other sister when she tried to ride.

With the unexpected media blitz, the Nych Family was lucky enough to see our place on the news. How many people can share such boasts? Fortunately, it was the first time we mowed the grass all year. I recall putting my back out when I shoved all the odds and ends (mostly odds) into the confines of the garage. It’s true about the camera adding ten pounds, for the crew did a good job making Gertrude’s starving horses look happy.

Regardless, animal rights activists were outraged and set forth relentless efforts to locate and execute the perpetrator. Public support and the Humane Society raised a $6,000 reward for the person with information leading to the arrest. Although I had nothing to do with it, for this kind of money I was ready to turn myself in and enjoy the reward.

Tourists would pull in our dirt driveway, dusting up their shiny luxury cars. The travelers would instantly inquire as to where Kahlua once roamed wild and free. I pointed towards the small, crumby barbed wire fencing job, completed by Gertrude’s unfortunate son. The likes of which were only slightly larger than Gertrude’s closet. I shared, “There.”

“Oh…” was a typical response.

Dust around the Nych Farm eventually settled. Following the rural Pennsylvania version of the Crucible, many began to suspect Gertrude’s television speeches were a bit contrived and came not from her heart, but her derrière. I believe she requested all checks to be made payable to Gertrude and was so kind, she provided a home address.

Dad was the last to see the news crew and harvest the fame, which is an uncommon crop on our farm. As my father was bailing hay one afternoon, months since the last time Kahlua tragically stumbled into a groundhog hole, a white news van pulled alongside the barn. Mind you, when my dad is bailing hay, he is not exactly dressed to be on the big screen. The shirt and tie reporter hesitantly approached the sweaty, flannelled man.

“Sir, are you familiar with Gertrude and her story of Kahlua?” spouted the reporter.

“Yep.” Dad nodded.

Excited, the reporter continued, “It has been a very long time since the mysterious death and nothing has been uncovered.”

“Nope.”

Startled a man could be of so few words, the reporter prompted, “Any comments I can share with our viewers at home?”

“Slow day?” asked Dad.

Letting out a deep breath, the reporter sighed, “Yep.”

Everyone had felt so bad for Kahlua and, even more so, for Gertrude. The Humane Society used a fraction of the reward money to replace Kahlua. Now I’ve got a new old horse running around behind my house. You can come over and ride Martini anytime.

Marshall Nych’s habitat is a family farm in New Wilmington, PA. When Marshall isn’t writing outdoor humor, he is an elementary teacher misguiding the youth of Mercer County. Although Nych has fished 15 states and 4 countries, his best catches remain his wife and daughter.

Obscure Scout Badges

Cub Scouts, a wonderful organization, is the cotton swab opening our youth’s ears to the call of the wild. Too often, the call is dropped at some point in a young man’s life. Cub Scouts teaches valuable outdoor skills and instills character. As boy turns to man, he may find these to be advantageous for this adventure that is life.

Cub Scouts, a wonderful organization, is the cotton swab opening our youth’s ears to the call of the wild. Too often, the call is dropped at some point in a young man’s life. Cub Scouts teaches valuable outdoor skills and instills character. As boy turns to man, he may find these to be advantageous for this adventure that is life.

As a boy, I too was a proud Cub Scout. My only problem was the badge system, mainly the lack thereof I had earned. To me, the scout badges were much too tame and mainstream. I have developed a list of the more obscure scout badges I would have rightfully earned and proudly displayed.

There exist many badges dealing with starting fires. However, few are concerned with the importance of extinguishing the fire from your fellow scout or scoutmaster. Badge name: Personal Fire Extinguisher. If this unrecognized badge had been adopted, I’d have earned the starting and stopping flames badge simultaneously. Crispy Kurt, although he has been known to speak about me, to this day will not speak to me. I think he was jealous of my badges.

Cub Scouts should recognize the Most Lost Badge. The leaders of the scout world need to consider the survival skills, perseverance, and luck it took to achieve such a level of lost. If the higher ups ever went higher up themselves, for a remote mountain is an ideal place to get lost, this badge would certainly make its way to the top of the list for badge proposals.

Do not forget about the Running Badge. Everybody knows you don’t have to be faster than the bear, lion, or raccoon. You need only be faster than the scout or den mother beside you…or in my case, the one who was underneath me when the bump in the night lit my fuse and caused me to hurdle the entire troop.

There should also be a badge celebrating the one who eats the most s’mores. Although the commercials and manuals want you to believe otherwise, Cub Scout campfires are rare. Cub Scout cookouts are a nearly extinct creature. I had to take full advantage of this deep woods buffet while it was there. S’mores from my microwave lacked the charm and char versus the ones I made over those Cub Scout campfires. My single night caloric intake rivaled the number of stars we fluffy, sticky campers marveled at all night.

What about the Most Persistent Badge? Often my troop would simply whittle soap or twiddle thumbs. Someone, namely me, always had to keep the scoutmaster on his toes by begging for activities involving hunting, fishing, camping, or starting fires. Ironically, the very scout who initiated these endeavors was the very lad to somehow miss them due to punishment or scout probation.

Personally, I feel our culture has done an injustice to our youth by de-emphasizing healthy competition. A badge should honor those individuals who strive to be the best. I am referring to the scouts who use a Swiss army knife to think and/or cut outside the box in order to annihilate the competition. Since I was a boy in Cub Scouts, I was left to assume our opponents were the Girl Scouts. This is a logical, natural assumption. To loosen the grip our rival Girl Scouts had around the snack market, I decided to sell some tasty treats of my own. I sold bag after bag of my father’s jerky to raise funds and increase Cub Scout revenue. Apparently the Cub Scouts, unlike me, didn’t officially classify the Girl Scouts as our arch nemesis. Things got even worse when Dad noticed his stash dwindling. Hence, at the ripe age of nine, I discovered the hard way it is illegal to sell venison and other wild game (even for a non-profit organization).

Another scout badge should reward the most dedicated of Cub Scouts. I gave up homework, mother’s homemade meals, and farm chores to completely devote my efforts and energies to the scouts. After having some of those home cooked meals, some of my fellow scouts thought I was homeless. My teachers didn’t buy the “great sacrifice” speech pertaining to their homework either.

Each year the Cub Scouts would gather in the den mother’s garage or basement to make bird boxes. My contribution to this task was not fully appreciated. While all of the other scouts measured board and hammered nails to create what they argued was a birdhouse, I went out in search of actual birds to inhabit them. Never mind the small detail I was armed with my reliable Daisy BB gun. I still think most boxes resembled a coffin more than a house.

Much like the military, Cub Scouts should offer badges and incentives for recruitment. I enlisted many “characters” to the Cub Scouts. For some reason unknown to me, these questionable friends of mine became misfit, rogue scouts. I was not to be blamed. Plus, hearing I had been officially asked to leave the organization, many more really good kids signed up on the spot. Directly or indirectly, I must have introduced dozens of young men to the Scouts.

Looking back now, I am proud to have been a Cub Scout. Although we did more shouting and pouting than actual scouting, my experiences helped shape the man I have become. I would hope today’s Cub Scouts have the opportunity to earn some of the more obscure badges I have suggested. Perhaps, if they lift the permanent ban, my children can someday participate too. I am confident you can think of a couple badge ideas of your own. Let us hope Cub Scouts of the future continue appreciating nature and doing good…or at least start selling some of those tasty cookies like the Girl Scouts.

Marshall Nych’s habitat is a family farm in New Wilmington, PA. When Marshall isn’t writing outdoor humor, he is an elementary teacher misguiding the youth of Mercer County. Although Nych has fished 15 states and 4 countries, his best catches remain his wife and daughter.

Thorn in My Side

“ Oh hell!” shouted Tough Guy. To hear Tough Guy holler such an obscenity falls anywhere on the reaction scale ranging from as serious as a bear trying to kick in the backdoor to as trivial as Tough Guy guzzling the last beer. I had a strangely conditioned childhood.

“ Oh hell!” shouted Tough Guy. To hear Tough Guy holler such an obscenity falls anywhere on the reaction scale ranging from as serious as a bear trying to kick in the backdoor to as trivial as Tough Guy guzzling the last beer. I had a strangely conditioned childhood.

Tough Guy commanded, “Someone with good eyes get over here – now!”

Having experience with these situations, I visualized that 20/20 vision would be labor intensive. Apparently Grizz and Lou had picked up these classic tricks, for the three of us began squinting.

Tough Guy huffed into the room, clearly seeing three squinters. Since I was the closest relative (sadly one cannot get any closer than son status), I needed to take my blind disobedience one step farther – acting. I leapt from my seat and started walking into walls. Lou, grasping the genius of my ploy more quickly than Grizz, followed suit. Lou added some respectable improvisations of his own, using the wall to feel his way to the dinner tray, which he then casually unfolded to double as a walker.

Tough Guy appeared to be clenching a shiny, metallic something at his side. Since I couldn’t positively identify it through my squint, I assumed the worst. What was my father planning to do with a bowie knife?

“One of you get over here and pull out this here splinter. I can’t reach it!”

Unless Dad was using the blade to lift the thorn or to rally splinter support, the bowie knife may have been a pair of tweezers.

Grizz was still stuck in a frozen squint on the couch, like a possum playing dead. Tough Guy didn’t fall for it. Something about a kid wearing glasses while squinting didn’t add up.

Looking for a distraction from this extraction, I started cooking some hot dogs. Lou watched. It was during this wiener roast we overheard the dilemma. Tough Guy, during a hunt from either last year (or the season before), must have picked up a nasty splinter. Lou and I cheerfully reveled in the fact we were liberated from performing such a surgery. Upon learning the splinter’s location, we added jubilant dance and joyous laughter to our celebration.

I could identify with the splinter, for Tough Guy had labeled me a “thorn in his side” during many projects, hunting trips, fishing excursions, and the like consistently throughout my many years as his son. One difference, this thorn wasn’t in his side…it was closer to his rump. Dad had called me one of those on special occasions when he was especially angry with my listening skills, subpar performance, or me. Grizz and Tough Guy looked like bonding primates as they hunched over the front porch, nephew carefully examining and grooming uncle’s backside.

It was then Lou and I were subjected to the dreaded northern exposure. I’m not talking about an old television sitcom. To woodsmen, northern exposure is the tense moment when a fellow hunter disrobes…taking off his shirt before, during, or after the hunt. Arguably, post-hunt exposure is the most gruesome and offensive. Although side effects from northern exposure include blindness, slurred speech, and psychological scarring, it is much preferred to than exposure of the southern hemisphere.

Thoroughly damaged by this spectacle, I reflected upon how Tough Guy has softened over the years. When I was a kid, my dad was the scariest man I knew. He would have never let anybody touch or help him. Along with band-aids and mirrors, tweezers were considered feminine products. The former Tough Guy would have just stared the splinter out, or even better, pushed it in deeper to have his toughness and meanness fueled by the pain.

One time in particular, I recall being the proverbial thorn in my dad’s side. To this day, I am trying to repress this sliver of memory. It was my first big hunt. Granted, I had been on hundreds of small hunts, running all over Grandpa’s farm with my BB gun shooting sparrows, rodents, livestock, windows, and anything else that would let me get close. However, this would be my first time hunting the big woods from which Pennsylvania got her sweet name. Had William Penn been inspired from the very farm where I have perspired, we may be living in Penncoop or Pennpigpen or Penndilapidatedbarn. None have the same flare as Pennsylvania.

Normally, young boys experience their first big hunt in big woods when they are twelve, licensed, and legal. Not me. Mom, desperately in need of a day off from her problem child, assigned Dad to babysit his just-turned-nine son one fall Saturday. Big problem…Dad hunts the real woods up in the mountains on autumn weekends. Rather than reschedule or cancel the trip my father had planned with my older brother Nathan, it was decided to drag the 9-year-old boy (me) alongside the Nych hunters. Dad had high hopes. Tough Guy wanted 2 men and a boy to return home as 3 men. I was quite satisfied with simply returning home.

Since my short legs couldn’t keep up with the rough ruffed grouse hunters, Dad had to pick from three options: slow down, carry me, or abandon me. Like so many game show contestants before him, Tough Guy chose door #3. Unnerved and unlicensed, I sat under an oak tree.

“This spot looks good as any,” my father said after hiking me miles from the nearest road, even further from the nearest hospital. Dad strategically set me under an oak tree with explicit directions, “If ya’ see a squirrel, pop ‘em! Limit’s six, but whose countin’?”

It was not the squirrels I was concerned about during the following hours of fits, trembles, and shakes. Lack of heat cannot take credit for my shivering, for it was a pleasant day not a degree below sixty. As occasional acorns plopped among nature’s blanket of leaves beside me, I began to feel I wasn’t the only nut in the woods. Do bears like to eat acorns?

Contemplating the answer, I grew even more worrisome. I was unpolished on bear biology. I mentally rifled through the many books I had read about animals up to this early, too-young-to-die point in my life. What do bears eat? Sadly, none of the ABC or pop-up books extensively covered Ursus americanus’ diet with helpful details. The only bruin delicacy I was familiar with was 9-year-old boys.

Some Christians are able to recall the exact moment they discovered their faith. Often, the enlightenment is during one of life’s highs or lows. One may find their faith upon reaching the summit of a life-long journey or while walking down a road of sin. Others may have experienced faith during times of deep sorrow, such as a loved one passing. Not me! Sitting under that oak, I made a deal with God. So long as He didn’t show me one of the big, hungry bears He had created, I promised to clean up my act and walk a straight line the best a nine-year-old kid could.

The .22 caliber rifle, a petty pea-shooter to any bear, whimpered upon my lap. My thoughts drifted to the possibility of having to take down a charging beast with this limited artillery. Big bear in big woods charging a little boy with a little gun. My shaking knees had jarred the rifle so badly, I’d bet the sights were off anyway. I considered climbing the tree, but feared I’d just look like an overgrown, irresistible acorn to a browsing bruin.

During my first big hunt, which was not a good first impression, I’d hear occasional shots in the distance. Although they were likely Nathan missing grouse or Dad dropping some species of animal, I tried to stay positive (that’s what the survival guides said to do). I told myself perhaps a pack of rogue poachers had stumbled into an entire cave of famished, killer bears. Just as the den of evil creatures emerged to come eat me, the outlaws wiped out every last one of them.

Such delusional activity and mind-numbing stress continued. Days, perhaps weeks later when Tough Guy had returned, only the hollow shell casing of the happy boy he abandoned remained. I no longer derived amusement and joy from playing with G.I. Joes, Lego’s, or other boyhood distractions. I avoided men for many years, naturally being drawn to the non-hunting, non-abandoning qualities of women, such as my mother, grandma, or Barbie.

I endured physical changes as well. Besides the unexplainable new twitch, many of the brown hairs on my head had faded, while other hairs sprouted in strange, unexpected places. Fear is the only catalyst I can fault for this loss of pigment and gain of unsightly patches. A graying fourth grader with back hair is the most bizarre sight. However, salt-and-peppered kids probably do better on their history tests. Although, at the time, I speculated these were side effects from the severe shock and being too afraid to move. It was not until later, I accepted the fact I had morphed into man.

Realizing the possibility of irreparable damage, Tough Guy wouldn’t admit to his 9-year-old, snot-nosed kid he had in fact misplaced him. These confessions could only be told to a fellow man. In the days following the big hunt, Dad saw the masculine changes right before his eyes. My father decided to let me in on the little secret.

Sitting on the side porch, Dad and I were enjoying the unmistakable sounds and smells summoned by autumn twilight winds. Tough Guy cracked open a beer. Had I been twelve years older, I’m sure he would have offered me one. After swallowing his frothy sip, Tough Guy said, “To be honest,” pausing then looking away, he confessed, “I thought I had lost you myself.”

Although I hadn’t spoken in a week, I mustered up the strength to ask, “W-h-hat?”

Dad continued, “Couldn’t remember what beech tree I set you under.”

“B-b-beech?”

Tough Guy went on, “I says to myself, maybe a bear got ‘em! I had been seein’ fresh tracks all day.”

“H-h-huh?”

Dad was always a man of few words. Hence, this conversation and its several lines of dialogue had become too strenuous…he had to give the story an ending. Father, feeling he had lost his middle child forever to the deep woods, finished his story. “Then, ‘membering I put you under a big oak not a beech, I turned the truck back around to come and getcha’!”

“Y-y-you had left in the truck?” I asked.

Never much for happy endings, Tough Guy concluded, “Oh hell!”

Hello

My name is Marshall. I am an elk-a-holic.

It used to be my addiction prompted a two day binge westward. To be amongst a harem, I’d be forced to travel to Colorado, Wyoming, or other wild, western location. Typically, the only one I could talk into such an addiction was my father.

Thanks to Keystone Elk Country Alliance (KECA) and their fine visitor’s center in Benezette, Pennsylvania, I now only need drive two hours to be surrounded by one of the most flourishing elk herds in the country.

Thanks to Keystone Elk Country Alliance (KECA) and their fine visitor’s center in Benezette, Pennsylvania, I now only need drive two hours to be surrounded by one of the most flourishing elk herds in the country.

Growing up in a dry town, meaning one without elk at all, I had grown accustomed to whitetail deer. Though I am a whitetail deer hunter from womb to tomb, I must offer a few confessions. When deer and elk are seen cohabitating the same woods, deer look a lot like frisky little squirrels and elk look a lot like elk. For such sportsmen and women more familiar with whitetail than wapiti, allow me to compare the Cervidae family cousins.

When a whitetail buck tickles a tree come autumn, we refer to the delicate dance as a rub. Less gentle, a brute bull elk unearths and uproots entire trees. Any eyewitness would testify the action as downright timbering or clear cutting.

Both the elk and deer are social, vocal creatures. This is about where the similarities abruptly end. The buck, on his best day, may flirt with a few does. A bull, like the pimp of the pines, has a harem of 20 or more cows. The whitetail grunts, a vocalization not far removed from a sound one might expect from various species of livestock on a farm. A bull elk’s bugle, audible for more than a mile, is seemingly capable of lifting fog. The wapiti’s song pierces the autumn air as it bounds from one mountain top to the next.

Another area of interest is antlers. Whitetail racks are described in total points. A specimen both widely and wildly popular is an 8-point. However, a typical bull with “8 points” would be called a 4 x 4. Such an accurately vivid description brings to mind the sound and strength of a full-sized pickup truck. Truly magnificent bulls often reach 7 x 7 (seven by seven) or greater.

Then there is mass and size. A whitetail deer can tip the scale just larger than my first grade teacher – Miss Take. No one ever accused her of missing lunch. I’d bet during the rut she was close to 300 pounds. A mature bull, weighing in at more than 1,000 pounds, would send the entire 1st grade class of25 flying from the teeter totter.

Then there is mass and size. A whitetail deer can tip the scale just larger than my first grade teacher – Miss Take. No one ever accused her of missing lunch. I’d bet during the rut she was close to 300 pounds. A mature bull, weighing in at more than 1,000 pounds, would send the entire 1st grade class of25 flying from the teeter totter.

Armed with such knowledge, Dad and I ventured east towards the Keystone State’s elk country. Pennsylvania is roughly 46,055 square miles. The country home to the PA elk population is approximately 850 of those squares. This equates to the following assumption: Pennsylvania residents, as they step out their back door, have a 1 in 54 chance of sharing their backyard with an elk.

Spanning portions of 6 of her 67 counties, there are an estimated 1,100 elk currently in Pennsylvania. A whopping 400,000 people take the pilgrimage each year to the Benezette area to see them. Three-quarters of these tourists time the trip between Labor Day and Columbus Day to coincide with the breeding season. It is estimated this eco-tourism rakes in 80 million dollars annually.

Not only is elk one of my vices, so too is gambling. I know of no greater lottery than the play for coveted Pennsylvania elk hunting tags. The lottery will set players back a mere $10.70. This is roughly $.70 more than the premium scratch off ticket currently lining my waste basket. This year, 124 licenses (25 antlers, 99 antlerless) were awarded. Doing the math with any degree of honesty or accuracy, one quickly learns the probability, unless you are immortal, is slim. With roughly 30,000 sportsmen and women chancing it for those 124 tags, odds are less than once-in-a-lifetime. But, if selected, hunters enjoy unmatched success rates. Those fortunate few who draw bull tags traditionally experience greater than 90% success rates. Slightly below, cow success rates are in and around 80%. Growing up on a cattle farm, I sincerely doubt I could do any better for bulls or cows on Grandpa’s back forty.

Once inside the KECA visitor’s center, I was immediately engaged by the entertaining, engaging, and educational materials. When I wasn’t salivating over the lifelike mounts, I stepped inside the 4-D Theater. Aside from my 10th grade report card, I didn’t even know there was such a thing as four D’s. My tour of this well-designed, environmentally friendly facility took place between peak morning and evening elk viewings. Guests from all 50 states and 43 countries have packed into this 12 million dollar, 8,420 sq. ft. phenomenon.

Waking up hours before I would have had I been working, my father and I were the first ones in the Winslow Hill Viewing Area parking lot both mornings. In addition to our dawn details, we spent an evening in and around the Woodring Farm Viewing Area. Conservatively, I witnessed 125 – 150 elk each of my two days. Though many were close enough, I didn’t bother asking any of them if they were repeats.

Waking up hours before I would have had I been working, my father and I were the first ones in the Winslow Hill Viewing Area parking lot both mornings. In addition to our dawn details, we spent an evening in and around the Woodring Farm Viewing Area. Conservatively, I witnessed 125 – 150 elk each of my two days. Though many were close enough, I didn’t bother asking any of them if they were repeats.

Be it book side or brook side in a library or landscape, I had seen and studied elk my entire life. Still, I learned a fun fact on my most recent September trip. Just after Labor Day, I was privy to a patent move experts call an “elk chuckle.” As the bull emits a distinct, unmistakable chuckle, so too does he urinate all over his body. Though I too have endured raging fits of laughter, I proudly have yet to chuckle myself.

Wanting to get as humanly and humanely close as possible to the aforementioned action, I signed up for a horse ride. A few times per evening, visitors can tour the elk behind a horse. As spots fill quickly, I was sure to arrive early. Eagerly, I jumped upon the horse like I had seen in my favorite westerns.

“What are you doing?” asked an official sounding voice.

At about this time the gaggle of elk viewers arrived to the scene. “Y’all know,” I answered, “fixin’ to lead this fine horse an eighth of a day’s ride here into the sunset and see some elk.”

“Oh yeah,” the gruff man chuckled, “this here is a wagon ride. Now dismount from the lead horse and take a seat on the wagon.”

As I dismounted, my right foot became stuck in the stirrup. Onlookers from the wagon giggled and snickered. Their wild children laughed at me too. Still, the wagon ride was unforgettable. About the only way to get any more intimate an elk experience would be to jump on the back of one. At least they wouldn’t have stirrups.

As with any fun outdoor pursuit, so too did this one have an end. To show the wife at home my gratitude, I wanted to get her a bottle of wine. Visiting a local winery, so close to the elk action the beasts likely crushed the grapes with their hooves, I scanned the racks. I was disappointed there wasn’t Bugle Trip or Rut Juice. I would have really loved uncorking a bottle of those with my wife.

The owner approached. Though she didn’t remember my father at all, he remembered her.

“Remember me from school?” Dad asked.

“We went to high school together?” she questioned, likely dialing the police with an emergency built into the bar.

“Yeah!” Dad huffed. Following a large helping of awkward silence, he continued, “Got anything with genuine, local flavor for my boy?”

“How original are we talking?” she smiled.

“I dunno,” Dad paused, “maybe your finest Elk Chuckle. Hey I want you to meet him!” he finished, summoning me towards the counter.

“Hi. My name is Marshall. I am an elk-a-holic.”

Elevation’s Revelations

By Marshall Nych

Shortly after learning to walk, children try their hand at climbing. Kids soon discover no limbs hold more adventure or offer a better embrace than those of a tree. Little changes when child morphs to adult. Bowhunting is nothing more than adult years imitating former years. I would argue happiness and height perched in a tree are directly correlated. I entertain and chase some of my most original thoughts, best daydreams, and most creative ideas while tangled amidst various species of hardwood. Perhaps something magical happens to the air a few stories off the ground or, maybe, the brain isn’t receiving sufficient levels of oxygen.

Shortly after learning to walk, children try their hand at climbing. Kids soon discover no limbs hold more adventure or offer a better embrace than those of a tree. Little changes when child morphs to adult. Bowhunting is nothing more than adult years imitating former years. I would argue happiness and height perched in a tree are directly correlated. I entertain and chase some of my most original thoughts, best daydreams, and most creative ideas while tangled amidst various species of hardwood. Perhaps something magical happens to the air a few stories off the ground or, maybe, the brain isn’t receiving sufficient levels of oxygen.

Regardless, no time finds me clambering more than October. Come the year’s tenth child, my personal favorite, I spend more time off the ground than I do on it. Local squirrels begin to think of me as an overgrown, awkward uncle. While speaking of my nuisance nephews, when I hunt deer I see squirrels. Logic suggests I should hunt squirrels to see more deer. Such are the whimsical epiphanies and nuggets of logic I stumble upon come archery season.

Relating to the aforementioned squirrels is another brand of rodent – chipmunks. I have observed an alarming abundance of chipmunk while on stand. Rigorous research estimates the Pennsylvania deer herd somewhere in the neighborhood of 1.5 million. I need to find that neighborhood. If the ratio of chipmunk to deer I personal endure is accurate statewide (12:1), this means there are roughly 18 million chipmunks scurrying and chattering about the Keystone state.

You are likely astonished by my height perception (taller cousin to depth perception). Once safely affixed to timber, I offer plenty more such reflections and philosophies. Twiddling my thumbs while waiting for whitetails, I have arrived at some of elevation’s revelations.

Scent Eliminators: My fellow archers strive for complete control over body odor. If the scent eliminating products bowhunters employ are scent-free, why do they have a distinct odor? Should scentless have a smell?

Deer Urine: One of the most important ingredients uniting male and female deer is the very substance causing a rift between human husband and wife – urine. Apparently in the cervidae world, emptying one’s bladder carelessly all over the place is not only socially acceptable, it is celebrated. Not so with homo sapiens.

Nocks: A penny’s worth of plastic is the pastor presiding over the marriage between arrow and bowstring. Scary thought. Any seasoned bowhunter knows the word nock refers more to the lifestyle of the archer – it’s a hard nock life. Hunting from the delicate balance that is a tree stand, the number of things to go wrong vastly outweighs the mere grains of what can go right. Nocks have shattered, fallen off, been too heavy, stuck to the string, and been too light. Newer models of nocks even light up, inevitably leading to frustration when they turn on at the inopportune time or refuse to illuminate when desired.

Arrow Rests: The two most popular varieties of rest are the drop away and the Whisker Biscuit. The former refers to the clumsy action of what happens to most of my gear from the stand – with some assistance from gravity, expensive gear drops away. I once fumbled a quiver full of arrows as a buck closed into range. The latter style rest, the Whisker Biscuit, describes the convenient snack leftover from breakfast amidst one’s beard.

Can Calls: Canned alludes less to the shape of deer calls and more to the quality of hunting on some television programs. Personally, I do not like the cylindrical design. Simultaneously, I once tried to open and drink an estrous bleat while calling a deer in with a Pepsi.

Grunt: If you sound anything like me climbing a tree, you needn’t purchase some fancy grunt call. Save money and make the sound yourself. As I am slinking up the tree my grunts and groans have frequently enticed deer. Come to think of it, I have called more deer in while grunting up the tree than grunting in the tree. Admittedly, I am uncertain as to whether they are drawn by the sound or the desire to heckle such a poor specimen.

Stabilizer: Most bowhunters immediately think stabilizers are the weighted nubs affixed to the ends of their bows. Such tools deliver balance during the shot. Companies need to figure out a way to attach a stabilizer to the actually bowhunter.

Safety Harness: This lifeline prevents accidentally falling from the tree stand. Ironically, the safety harness is also the bulky contraption preventing you from buckling your seat belt and the very cause of swerving into a tree. Not having been wrapped in as many cords since birth, officers will save you from the wreckage and exclaim, “Wow! This one is an astronaut or something!”

Quiver: The term is less noun than verb. Quiver is the side effect of buck fever often blamed for a complete miss. The hunter’s quiver forced a humble retreat into the quiver for another arrow.

Nocturnal: The typical bowhunter complains deer have inexplicably, irreversibly gone nocturnal due to daytime activity and increased hunting pressure. I have devised a way to combat such phenomena. If daytime activity makes deer come out at night, then nighttime activity should cause deer to come out during the day. I would recommend late night activities, ranging from midnight meanders through prime habitat to thicket poker nights with guys.

Deer Movement: The only deer movement I seem to inspire and/or witness results in a pile of what appear to be chocolate covered raisins.

Fashion: Likely one of the most unlikely concerns to bowhunting brethren, I recently received a fashion consultation from my hunting crew. The guys constantly rag on me about my rags and tease that I am too cheap to buy new camo. Donned in my time-tested, tattered and torn clothing, I descended the stand to help some buddies with a blood trail. Arriving to the scene, the group cheered in unison, “Hey, Marshall bought a fancy new ghillie suit! It’s about time.”

Imagine their surprise when I answered, “This isn’t a ghillie suit…”

Snack: Archery season isn’t all seeing deer and shooting at bucks. As the hands of time suffer from arthritis, one’s tank begins to empty. To fuel long sits on stand, I pack snacks. None are better than products of the cacao bean, especially the chocolate covered raisin or peanut variety. Such caloric cravings caused yet another revelation. Nonchalantly rolling raisins down the runway to my mouth, I fumbled nearly the entire box. Upon departure, I immediately looked for my sweets. It became apparent the dipped raisins I had dropped just 20 feet above now looked strikingly similar to the droppings deer deposit (see Deer Movement). I closed my eyes, held my breath, and tossed a handful into my mouth. I have regretted my hunger-driven decision ever since.

Snack: Archery season isn’t all seeing deer and shooting at bucks. As the hands of time suffer from arthritis, one’s tank begins to empty. To fuel long sits on stand, I pack snacks. None are better than products of the cacao bean, especially the chocolate covered raisin or peanut variety. Such caloric cravings caused yet another revelation. Nonchalantly rolling raisins down the runway to my mouth, I fumbled nearly the entire box. Upon departure, I immediately looked for my sweets. It became apparent the dipped raisins I had dropped just 20 feet above now looked strikingly similar to the droppings deer deposit (see Deer Movement). I closed my eyes, held my breath, and tossed a handful into my mouth. I have regretted my hunger-driven decision ever since.

Descending from my thinking chair, which happens to double as a tree stand, I quickly return to mediocre, mere mortal thoughts. Once grounded in day-to-day life, such revelations elude me. I trudge on knowing clarity will come again the moment I clamber the rungs to sit upon my throne. I, like many, am a philosopher of the hardwoods. I think, therefore I am. I am, therefore I hunt.

By Marshall Nych

Marshall Nych’s habitat is a family farm in New Wilmington, PA. When Marshall isn’t writing outdoor humor, he is an elementary teacher misguiding the youth of Mercer County. Although Nych has fished 15 states and 4 countries, his best catches remain his wife and daughter.

Going with the Grain

By Marshall Nych

As a boy, rarely did I do as I was told. School bells sounded to a young man daydreaming about the woods and waters. At heart, I was a wild creature confined by the classroom, tamed by a schoolmaster. Once home, chores were often overlooked to chase the very places I had daydreamed about all day at school. Mothers and teachers alike would inquire, “Marshall, why do you insist on going against the grain?” The expression, like other figures of speech, made little sense at the time. Still, there were men who not only led such lives…they did their best to encourage mine. Some were men I knew at birth, like my Dad and Grandpa. Others I would come to know during life’s later chapters. Such was the story of my father-in-law, Jim Harper.

Only when I reached an age my father entrusted me with gunpowder did I come to understand quotes about grains. Sure the pellets chambered in my airgun’s barrel seemed coated with some type of mysterious powder. Though it certainly wasn’t combustible, my delusions believed it to be diluted gunpowder. Admittedly, I was not to admire the art of reloading and handling gunpowder until the age of twelve. This was the year boys of Pennsylvania mysteriously matured into young men of the woods. I quickly came to respect the notion of “going against the grain.” Now a hunter, I delightfully adhered to a facet of my life I could finally go with the grain – reloading.

Only when I reached an age my father entrusted me with gunpowder did I come to understand quotes about grains. Sure the pellets chambered in my airgun’s barrel seemed coated with some type of mysterious powder. Though it certainly wasn’t combustible, my delusions believed it to be diluted gunpowder. Admittedly, I was not to admire the art of reloading and handling gunpowder until the age of twelve. This was the year boys of Pennsylvania mysteriously matured into young men of the woods. I quickly came to respect the notion of “going against the grain.” Now a hunter, I delightfully adhered to a facet of my life I could finally go with the grain – reloading.

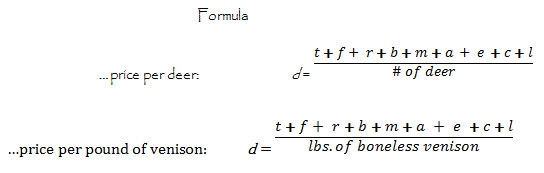

Reloading offers many advantages for sporting men and women. Positives range from the clear cost effectiveness to precision and accuracy. This pair of aforementioned pros of reloading are frequently written about and articulated in popular outdoor magazines.

However, truth be told, I am not a technical man who can boast producing the world’s most accurate loads nor a scientific man who can present state-of-the-art ballistics. My focus settled on a third joy of reloading – the bonds formed. Once nestled into a reloading den, the delicately precise relationship between the numerous ingredients is not the only ones present. Boys observe the hands of fathers who learned from grandfathers.

Chronologically, my first teacher was my father. Dad’s reloading room had been strictly off limits to a dangerously curious boy who had a tendency to play with matches. As each season passed, I grew more intrigued by the innards of the den. The ban was lifted the year I was a licensed hunter. I recall the hairs stand on the back of my neck as Dad commanded, “Come in here Marsh.” Once I began drawing breath again, I began to notice the detailed hunting maps adorning the walls, save the southern end. This wall was trusted with the important task of holding his guns. Strewn about on a thick hardwood table with green metal cabinets were reloading tools, dies, gunpowder, and bullets. The smells of this factory were something the olfactory of a twelve-year-old could never forget.

Chronologically, my first teacher was my father. Dad’s reloading room had been strictly off limits to a dangerously curious boy who had a tendency to play with matches. As each season passed, I grew more intrigued by the innards of the den. The ban was lifted the year I was a licensed hunter. I recall the hairs stand on the back of my neck as Dad commanded, “Come in here Marsh.” Once I began drawing breath again, I began to notice the detailed hunting maps adorning the walls, save the southern end. This wall was trusted with the important task of holding his guns. Strewn about on a thick hardwood table with green metal cabinets were reloading tools, dies, gunpowder, and bullets. The smells of this factory were something the olfactory of a twelve-year-old could never forget.

Dad reloaded most, if not all, the various calibers at one time or another. There was his preferred pistol, the .44 Magnum. Both my father and his favorite actor Clint Eastwood packed this caliber. As a boy, I could scarcely discern between the two. Still, Dad truly made his mark as a hunter and reloader with Pennsylvania’s state bird in the sights. A ruffed grouse skillfully to hand was few and far between, even for the guys who knew what they were doing. My father was one who could out walk his dog. He limited most trips. In fact, Dad’s best year claimed 26 birds.

I still remember the reloading press. The shotgun hulls were always red. Though my father was a frugal man, Dad freely shared his shells with his three sons. All of whom suffered itchy trigger fingers. Upon missing the first few flushes, I’d playfully accuse, “What’d ya’ forget the lead when you reloaded this batch?” Dad would quietly grin then promptly drop the next bird to take flight. I watched this man swing on a grouse like a professional ball player hones in on the ball. On one hand, I can count the number of trips I lucked into more grouse than my father. Countless are the times I admired his reloading den, perseverance, and inhaled wafting gunpowder.

On my best day I was only a good grouse hunter. Still, the competitive streak of a young man in peak physical condition admired how Dad was still best in the grouse woods. Though I was good at grouse, I honed my skills until I became great at deer hunting. It was Grandfather’s hands who taught to shoot sure and steady with the rifle. Those determined, calloused hands, when they weren’t working the farm, were hunting or reloading his .30-40 Krag. Though less than 40 grains of powder, the gun held more sentimental value than a boy could possibly understand. Older brother Jule, a soldier during World War II, passed down the military rifle to his brother Adam, who ended up my grandfather. Though I recall Grandpa grumbling about the difficulty of tracking down dies or materials for the .30-40 Krag, I never once heard Papa complain about hunting, farm work, or anything other obstacle in life.

To a man as strong as Grandpa, grain had two distinct meanings. Grains referred to his livelihood from planting to picking. But, once the harvest had concluded, Grandpa measured a different grain. The patriarch of my family planted a 180 grain bullet atop 36 grains of powder. Like pulling the tractor perfectly into the barn, Grandpa would seat the bullet into the bottleneck casing. Similar to his symmetrical rows of corn, my grandfather would line up the finished cartridges.

Grandpa and I, of the many men in the family who hunted, harvested the most whitetails. Though Grandpa took many antlered bucks, it was a doe he dropped with one of his reloads I will never forget. Getting upward in age, Grandpa was confined to shorter hunts closer to home. One such trip took place along a thick fencerow between his pastures and the property he graciously sold me. Seeing darkness and dogged drivers approaching, Grandpa began unloading his trusty Krag. Then, with only the round in the chamber, a doe surprised everyone when it rocketed out of the thicket. Knowing he had only one shot, Grandpa skillfully traced the deer’s movement with his .30-40’s open sights. At the report, at nearly the length of a football field away, the doe buckled like the dozens before it. Grandpa was 85.

My most recent teacher was my wife’s father. Ironically, I nearly asked Jim Harper’s permission for his daughter’s hand in marriage one day we happened to be on the range. We had been target practicing with some of Jim’s reloads. Not yet knowing his accuracy, I opted to wait for a later, safer occasion to pop the question. More than a decade later, I closely associate Jim with the outdoors, muzzleloading, and reloading. If you’re still wondering, Jim granted permission. We have since enjoyed many days afield chasing game and many evenings reloading. Our words echoed through his cellar reloading den. God willing, Jim will one day teach his grandson Noah how to reload a .54 caliber flintlock with 80 grains of FF and a lead ball.

I am now the proud owner of a fine shotgun Dad surprised me with the day I graduated college, the sentimental rifle Grandpa took to the woods, and an antique muzzleloader Jim gifted when I married his lovely daughter. I figure it’s a fine time to go with the grain and start reloading.

By Marshall Nych

Marshall Nych’s habitat is a family farm in New Wilmington, PA. When Marshall isn’t writing outdoor humor, he is an elementary teacher misguiding the youth of Mercer County. Although Nych has fished 15 states and 4 countries, his best catches remain his wife and daughter.

A Survival Guide for Minnows

Cast number one-thousand, two hundred eighty…same result as cast number one – nothing. Fishing with my younger brother Ryan just the other day, catching our usual limit of invisible, we started to discuss the hundreds of tiny dilemmas facing each cast into the fray. Every variable and possibility puts the favor in the fish’s corner. It seems any attempt that doesn’t land directly into a fish’s open, yawning mouth is ignored as if it were a book on Christmas morning or Brussels sprout on Halloween.